To explain what I’m doing here … we have to go back to the late 1990’s, when I wrote several articles for Goldmine Magazine. This one, in particular, was a blessing. It was an interview back in the day with Herb Powers, Jr., a record mastering legend. Here’s his current website.

Let me introduce you to Herb Powers, Jr. First, read the Goldmine article.

Let’s take a look at a vinyl record. 45, LP, it doesn’t matter. If you look at the dead wax, the area between when the last song ends and the paper label begins, you’ll find some stamper numbers, or maybe some alphanumeric code decipherable only to a record company insider.

But sometimes there’s a message inscribed in the dead wax. Almost as if just before printing, somebody slipped into the pressing room, took a nail and etched a cryptic message into the runoff grooves. Forget backwards masking, reverse artwork letters or barefoot strolls across Abbey Road. Vinyl graffiti in the dead wax may indeed be the last true conspiracy.

For many record collectors, discovering their album has vinyl graffiti is like finding an Easter egg. Some discs have been inscribed with messages from the artists, autographs, expressions of love or wry comments from the mastering department. The mystery messages could be gripes about the recording schedule, a statement about the band’s philosophy, anything.

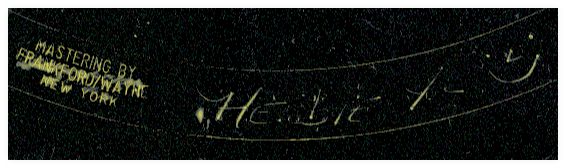

In the late 1970’s and early 1980’s, hundreds of 12-inch dance singles that were pressed at the Frankford/Wayne mastering plant in New York City contained the signature of Herb Powers, Jr. Go find an early 1980’s 12-inch New York City dance club record. If you look into the dead wax and see “Herbie Jr.,” along with an accompanying smiley face, you’ve found a record mastered by Herb Powers, Jr.

Powers was a former club DJ who joined Frankford/Wayne in 1976, learning the art of mastering records. “Back then the job entailed converting the music from half-inch tape to vinyl. I started putting my name on the dead wax on the first record, because I wanted to keep track of what I was doing. A lot of times, record companies did not give you credit on the records. It was a way for me to know that I actually mastered that record. It was also a way to tell that the record wasn’t a reproduction made by a bootlegger.”

By the late 1970’s and early 1980’s, Powers mastered some of the greatest New York City dance hits of the time – tracks like Run-D.M.C.‘s “Rock Box” (Profile 7045), UTFO‘s “Roxanne, Roxanne” (Select 62254), the Beastie Boys‘ “Rock Hard” (Def Jam DJ002), and Keith Silverflash‘s “Funky Space Player” (Silver Flash Funk 21801), among others.

Sometimes the dead wax graffiti was little more than his nickname, the smiley face and a stamp from Frankford/Wayne. But before long, Powers would put his wife’s name on the record… then his kids’ names… then messages about the record and its artist. “I started putting messages in around 1977, a year into my mastering career, when I got comfortable with what I was doing, comfortable with the client base that I had. For Tommy Boy, if you’re doing their first record, and you’re working together with the person and you say, ‘you know something, I really like this song. Let’s write something in the grooves about it.’ That’s something that happens as you get to know the people, the producers, the record company execs, the presidents, stuff like that. There were people that said they would not accept the record unless I enscribed something in there. Because they knew then that I did it. And on Cutting Records, I would put down Aldo, who was the owner of that label, he would always ask me to put his wife and kids’ names on the record. It was a good luck thing for him.”

In addition to his work with independent labels, Powers also mastered records for major labels like A&M, MCA, Columbia and RCA. “We had to keep the writing at a minimum with the major labels, because major labels were very picky as to what was in the grooves. Especially MCA. They didn’t even want you to write your name. They were very picky. They used to send us memos saying, ‘The only thing that should be in the groove is the actual scribe number of the record.’ But I would do it anyway. Some major labels didn’t care at all.”

If you own a copy of the Jonzun Crew‘s “Pack Jam” (Tommy Boy 826), you might see little Pac-Men in the runoff grooves. Once again, that was Herb Powers having fun. “Jellybean Benitez was working with a group called Nunk, on Prism Records, and one of their tracks had a lot of leadout. He wanted me to write almost a book. It starts at one end of the leadout and just kept going. We had a very sharp tool that looks like a dentist’s drill. You have to have a very steady hand and a good eye, to sit there and draw it in. We’re not using any magnifiers or anything, it’s all free hand. One small slip into the groove, and you’d have to remaster the entire record. That happened at least twice in ten years at Frankford/Wayne. It’s a very high pressure business – you don’t want mistakes, because you don’t have time to do it again.”

And one day, when Powers took a week’s vacation, another masterer at Frankford/Wayne enscribed their own contribution to the Herbie legend. “I was on vacation, and Tom Coyne had to cut Run-D.M.C.’s “Hollis Crew” (Profile 7058) for me. He told me afterward, ‘Wait until you see this record, you’re gonna be so mad, I totally dissed you!'”

Written in the runoff groove was “Who is Herbie Jr.?” It even had a smiley face!

After ten years with Frankford/Wayne, Powers moved to another mastering plant, the Hit Factory. He now operates Herb Powers House of Sound, his own Manhattan mastering plant. “Because of being a businessman and having so much pressure on me from the managerial standing and engineering and clients and everything, my work load has increased dramatically – I hate to say it, but I probably won’t get a chance to cut any more. Cutting takes a lot of time, it’s a very intense skill. I’m trying to train my assistant to be as good as I was. There needs to be some new good mastering engineer who knows how to cut records. Just like I think there’s still a need for people to learn how to edit tapes with a razor blade. I have digital editors, I have the whole nine yards, I have computer editing systems, but I still walk over to a tape with a razor blade and people go like, ‘You’re gonna cut that?!?’ I say, ‘Hey, I’ve been doing this for 20 years, that’s how we used to do it.’

I’m from the older school, and I’m working with all the newer gear, and it’s a matter of trying to keep my guys that I have brought in here to know the old. If you know the old, you’re going to do better with the new.”

Who knows? That smiley face might return to the runout grooves someday.

Okay, that was fun. And by the way, Herb Powers Jr. is still in the music business; he’s the owner and operator of Powers Mastering Studio, the link to which is here.

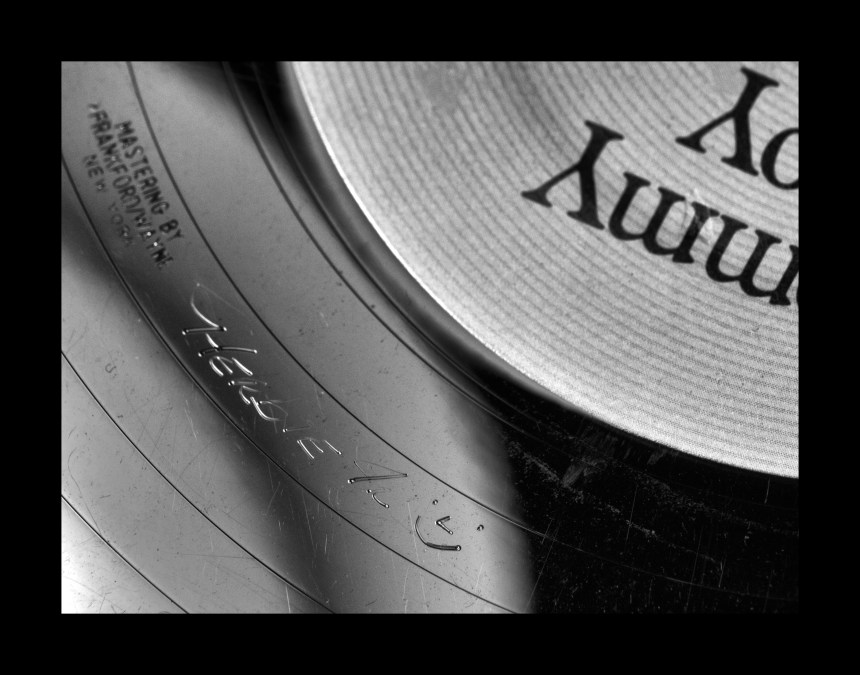

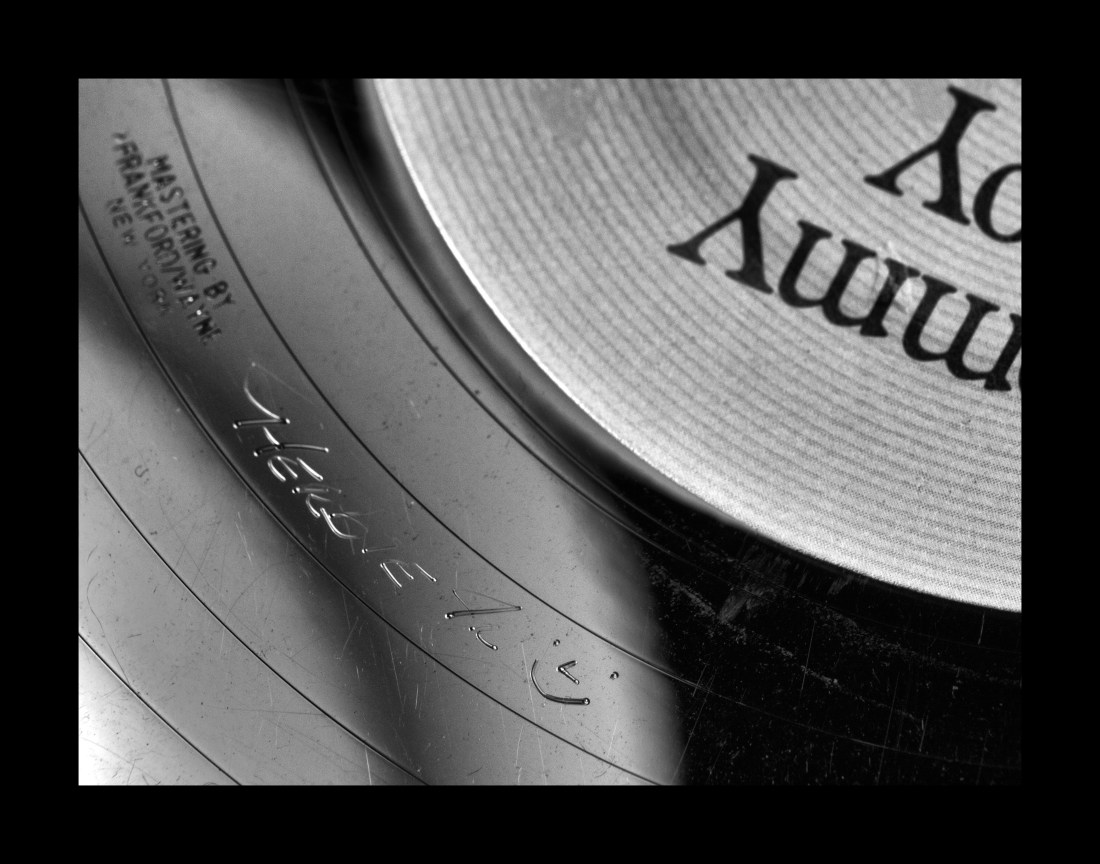

And that graphic you see at the top of the blog post?

I did that way back in the late 1990’s. Of course, back then I used a yellow china marker to color in the runout groove, and then wiped everything off with a soft cloth. And I photographed it with my (checks notes) Nikon Coolpix that could take a maximum of (checks notes) 1 high-resolution photo.

Of course … this gives me an idea.

And you know me … I love ideas.

I don’t have my voluminous record collection any more, but I checked through what I had. Surprisingly, I did possess three records that were mastered and scribed by Herb Powers, Jr.

Ooh, if I could photograph these with my modern camera equipment, it would look totally swank.

But how to get that vinyl properly photographed without resorting to china markers or baby powder or some other cockamamie etchings?

I placed one of the records – a 1983 dance track called “Pack Jam” by the Jonzun Crew – on an easel and lined up my Medical-Nikkor 120mm f/4 lens to capture as much as possible.

But each photo contained reflected flash brightness. Couldn’t get the shot I wanted.

So I turned off the Medical-Nikkor’s flash ring, and tried adding a spotlight out of range.

And after a few tries …

I got this.

Hello, short pile. Welcome to Competition Season 2026. I’ve got the signature, the company stamp, and I even snagged the little smiley face.

And no china markers were harmed in the process.

Yeah, this really feels good. This is worth it.

Definitely worth it.

I remember how delighted I was the first time I noticed this kind of message in the dead wax on a vinyl album. So cool! Well reported, Chuck! ~Ed.

LikeLike